The Soul Cut #04

by Etienne Delbiaggio | September 27th, 2025

During my third year at the CISA film school (back in 2019), I remember having an informal conversation with my editing professor. In her opinion, the emotion of editing lay primarily in rhythm. When I asked her to explain exactly what she meant, she replied that she didn’t interpret rhythm in a strictly schematic sense, but rather as harmony—something that can shift and evolve, shaping in its own way the sensations (or emotions) that draw in the viewer.

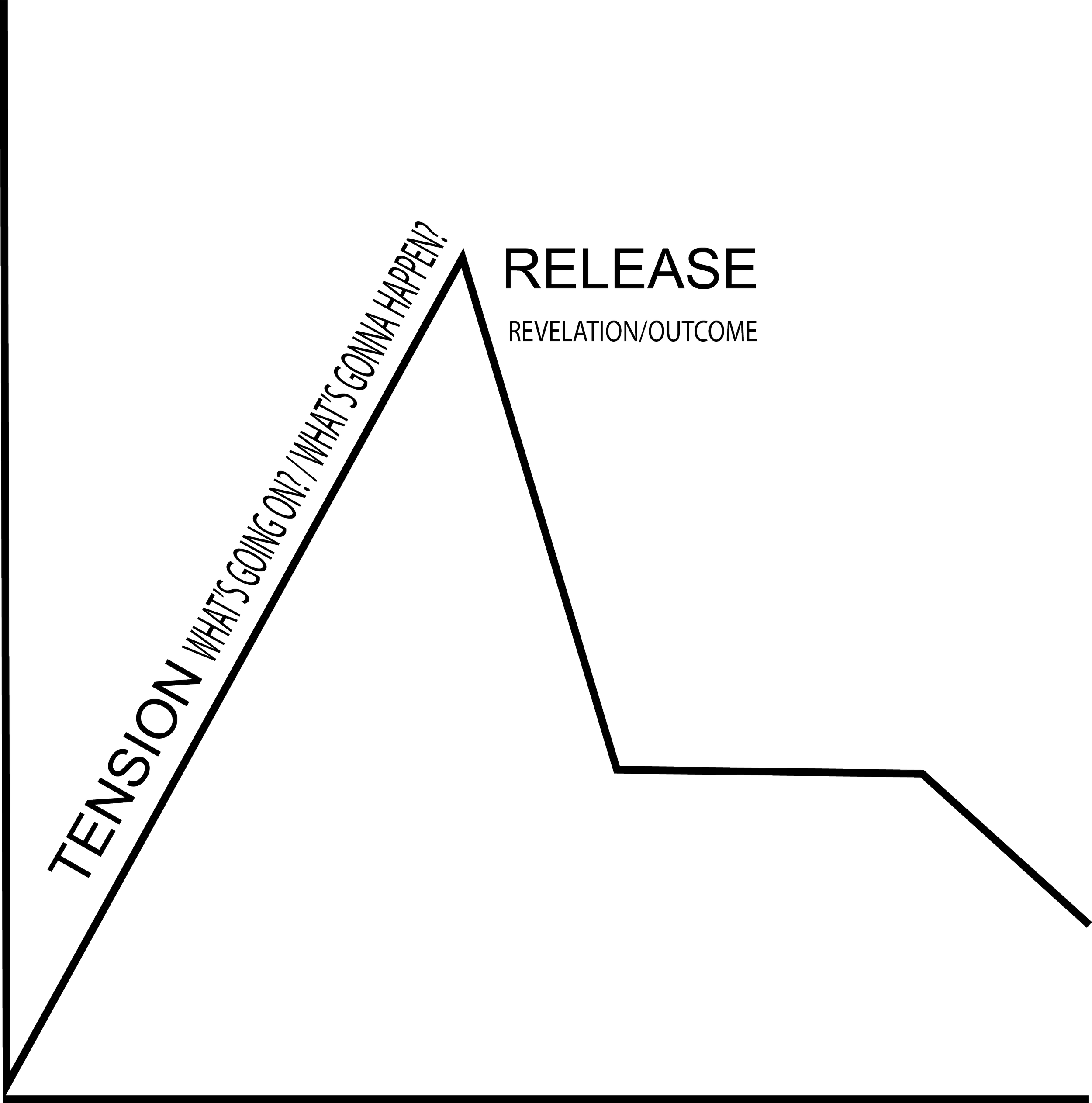

I found it curious that she used the word harmony, because in my personal view I see rhythm as a concept of tension and release: what to keep and what to sacrifice, or how long to hold and when to let go. This way of thinking about rhythm is rooted in musical theory, where certain chords (often called “suspended” or “sus” chords) or certain combinations of “classic” chords create a sense of tension, while others bring resolution. This feeling doesn’t reside in any single element but depends on how chords are combined, on repetitions, variations of tone or key, which—thanks to the internal properties of each chord—generate a flow of tension and resolution.

The rhythm

As in music, in cinema every scene has its own tension and release. Not only in moments of suspense, but also in the expectations it builds or the dynamism it creates within the work. Every shot is like a chord in itself, one that I can choose to pair with another—creating tension and its release, deciding what to hold on to or sacrifice in the action.

Every film has its own soul, its own personality (or style) that sets it apart from any other, even from works within the same genre. Just think of how The Shining (1980) by Stanley Kubrick (1928–1999) differs from other horror films, especially in its use of rhythm to make the viewer feel the slow descent into Jack Torrance’s madness, in contrast to today’s jump scares. It’s interesting to note how this descent is also accentuated through editing: by means of long dissolves and by holding the actors’ changes of expression in frame.

The decision to let the characters’ shifts in mood unfold naturally makes them more believable—especially in a scene like the one mentioned above, where we witness a disturbing event: the discovery of a stranger inside the hotel, which should be housing only the Torrance family. In the time of a cut, we may lose a tiny part of the character’s changing expression, but the viewer has already been given the elements they need to infer what happens in that brief interval off-screen. Returning to the face reinforces even more the protagonist’s desire for the woman in question, while also maintaining consistency in the pacing of the action.

This approach not only enhances the actor’s performance but also follows a kind of storytelling that strives to feel as natural as possible. The tension grows exponentially because the character is not reacting as one normally would upon encountering a stranger in a closed hotel, and even more so given that she is the prime suspect for the bruises on the boy’s neck. The scene continues with a slow rhythm, in a static wide shot, relegating the viewer to the role of a passive observer, until the release comes when the sense that something is wrong is finally revealed through the cuts.

But this film has its own precise style, one that tries to make the impossible believable. To achieve this, the editing remains as faithful to reality as possible, sacrificing very little. By contrast, there are films that sacrifice coherence in favor of a more immediate effect.

In a poker game, for instance, one of the protagonists provokes a Native American opponent. In the frame where the offended character takes off his sunglasses, his head is turned one way, but when we cut back to his close-up, he’s already facing the protagonist. This might have been dictated by practical necessity, yet the rhythm still works. Hell or High Water is essentially a drama with strong echoes of action cinema, so in a scene where the aim is to build tension through a quick, back-and-forth rhythm, it’s possible to sacrifice continuity for the sake of emotion.

How is it possible to make these sudden shifts believable to the viewer?

Because the cuts mimic the mental process of attention. The cuts and the choice of shots—with their internal characteristics and their relation to the story—are like the director’s hand guiding the viewer toward details that carry them into the intended emotional state. If the story calls for a fast rhythm to highlight an emotion (tension in Hell or High Water) or a slow rhythm (dread in The Shining), what matters is that the choice is deliberate and functional to the chosen style.

Especially in fiction, audiences don’t expect to see a literal representation of reality, but they do demand to believe what they’re watching. It’s therefore crucial to understand that when you work with details and cuts, you are directing the viewer’s attention toward an emotion they cannot escape. On the other hand, when you work with wide shots, you allow them the freedom to choose what to focus on. Another point is that if you make a cut that lacks real-world continuity, it becomes an artistic choice by the director—one that the viewer will try to accept (as will be shown in later chapters).

As with music, I don’t personally have a precise measuring tool for interpreting rhythm. I watch the footage and start to feel the direction it should take after assembling a first cut. You have to experiment until you sense that what you’ve built feels credible.

CREDITS:

Stills from The Shining, by Stanley Kubrick, The Producer Circle Company, Peregrine Productions, Hawk Films and Warner Bros. (1980)

Stills from Hell or High Water, by David Mackenzie, Sidney Kimmel Entertainment, OddLot Entertainment, Film 44, LBI Entertainment (2016)

My name is Etienne Del Biaggio. I am a film editor, self-taught animator, and composer of original soundtracks based in Giubiasco (Ticino, Switzerland). After graduating in editing and video post-production from CISA in Locarno (2019), I collaborated with Béla Tarr on Alma by Dino Longo Sabanovic, presented at the Locarno Film Festival. From 2022 to 2023, I worked as lead editor at Fiumi Studios, producing documentaries and corporate videos for clients such as Siemens and EOC Ticino.

Alongside editing and music, I have developed skills in graphic design and animation, creating several animated short films. Beyond these passions, I also enjoy sharing my personal reflections on film editing through my blog The Soul Cut, with the hope of inspiring others to explore the subject.