The Soul Cut #03

by Etienne Delbiaggio | September 18th, 2025

When I edit a film, I see it as a work in its own right, with a soul and a “character” that distinguishes it even from similar or related works. Take, for example, Gus Van Sant’s Psycho, conceived as a shot-for-shot remake of Hitchcock’s original, and compare the two different interpretations of Norman Bates by Anthony Perkins and Vince Vaughn. Even though the intention was to reproduce the original as faithfully as possible, the actors are not the same person. Two separate lives, two different generations and life experiences—this alone is enough to set the two films apart (in addition to other factors that will be discussed later in this blog).

“What do we want the audience to feel?” asks Walter Murch, when, in his book In the Blink of an Eye, he lays out his personal set of criteria—known as the “Rule of Six”—for making a cut that feels fluid and natural to the human eye:

Emotion over everything

Emotion

Story

Rhythm

Eye-trace

Two-dimensional plane of the screen

Three-dimensional space of the action

Murch explains that emotion should always be the element one strives hardest to preserve when making a cut. If something has to be sacrificed for the sake of a good transition, one should begin at the bottom of the list and work upward—never sacrificing emotion. What the viewer will remember at the end of a film will not be the beautiful shots, the acting, the story, or the editing, but the emotion they experienced while watching.

Murch continues by asserting that if you can make the audience feel what the original intention was, then the work has been executed impeccably and everything possible has been done to achieve that goal.

A craftsman is typically seen as someone with great technical skill in their trade, often imagined as an elderly figure carrying a toolbox full of manual instruments, able to select the most suitable tool to shape the material and achieve the final result. Daniele Maggioni, professor of Directing in my third year, used this example to illustrate to the class how an artist in cinema works with materials that are not usually tangible: emotions.

The author is a craftsman who carries with him a cultural and experiential toolkit that becomes his set of instruments. He learns to use (and to calibrate) them according to the needs of the project and the goal he wishes to achieve. This has always served me as a personal reminder before sitting down at the computer: one must have solid technical knowledge of editing, but the outcome should not be a display of one’s virtuosity. Rather, it should be the act of putting one’s technical knowledge in service of the most fitting emotion one seeks to convey.

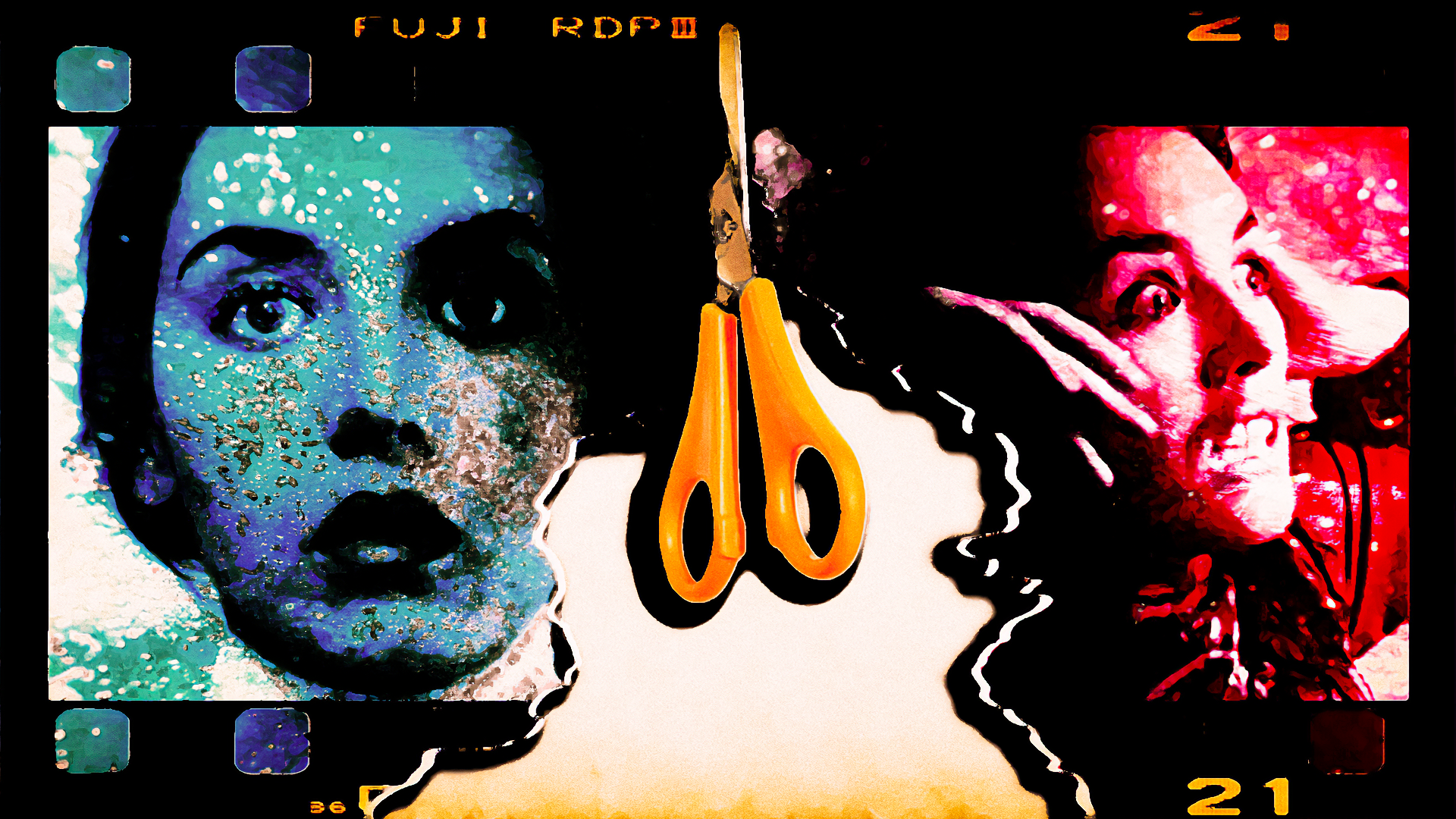

One of the scenes that struck me most from an acting standpoint comes from Possession (1981) by Andrzej Żuławski (1940–2016), where actress Isabelle Adjani delivers an extraordinary modulation of facial expression, as illustrated below, moving from left to right.

I was so impressed by her performance that one of my first thoughts was relief that the shot had not been cut, allowing me to witness the full transformation of her expression. Even though no action occurs within the frame, paradoxically, the decision not to cut and to let the emotion unfold naturally is, in itself, already an action.

As an experiment, let us try cutting the shot and adapting it to the story’s context to see what kind of reaction it might provoke: the scene depicts a marital quarrel between a couple in crisis. Suddenly, the woman slaps the man, and he asks her to do it again, triggering the reaction shown in the film’s original cut (see above).

If we cut to the husband’s face just a moment before he urges her to repeat the slap, and insert it only after showing the woman’s astonished expression, we create a brief moment of suspense. The viewer may be led to believe that the man will retaliate violently in response to the slap, as suggested by the woman’s frightened face. But by then cutting back to the husband urging her to strike him again, we overturn the audience’s expectations.

If, instead, we preserve the original sequence but enter on the woman’s face when her expression is at its most severe, the intentions take on an entirely different meaning. Now she is a determined woman, showing no regret for her act, and the husband’s invitation to repeat it creates the impression of a perverse game between the two. A small change has already created a new (though brief) interpretive state of the scene, and consequently, different expectations.

In the first two examples (the original and the first experiment), there is a glimmer of innocence on the woman’s face when her shot begins. In the third, by contrast, we are shown a character who appears resolute and almost malevolent. For this reason, it is crucial to know which emotion you want the audience to experience and precisely what story you want to tell.

CREDITS:

Photo of Walter Murch – Walter Murch working on Tetro in Buenos Aires (Beatrice Murch via Wikipedia)

Stills from Possession (1981), by Andrzej Żuławski, Gaumont

Quotations from In the Blink of an Eye, by Walter Murch, published by Silman-James Press

My name is Etienne Del Biaggio. I am a film editor, self-taught animator, and composer of original soundtracks based in Giubiasco (Ticino, Switzerland). After graduating in editing and video post-production from CISA in Locarno (2019), I collaborated with Béla Tarr on Alma by Dino Longo Sabanovic, presented at the Locarno Film Festival. From 2022 to 2023, I worked as lead editor at Fiumi Studios, producing documentaries and corporate videos for clients such as Siemens and EOC Ticino.

Alongside editing and music, I have developed skills in graphic design and animation, creating several animated short films. Beyond these passions, I also enjoy sharing my personal reflections on film editing through my blog The Soul Cut, with the hope of inspiring others to explore the subject.